By Lida Prypchan

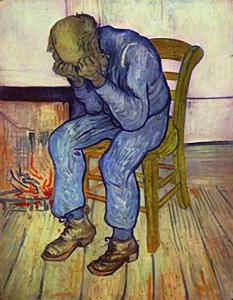

Although it appears that the two months between the arrival of Paul Gauguin at Arles and his time with Vincent van Gogh were largely two of the happiest months of van Gogh’s life, by December 23, 1888, it had ended in disaster. Whether precipitated by an argument with Gauguin, his feelings of inadequacy and fear of abandonment, or mental illness that van Gogh could no longer hide, the end of 1888 found Vincent van Gogh near death.

Although it appears that the two months between the arrival of Paul Gauguin at Arles and his time with Vincent van Gogh were largely two of the happiest months of van Gogh’s life, by December 23, 1888, it had ended in disaster. Whether precipitated by an argument with Gauguin, his feelings of inadequacy and fear of abandonment, or mental illness that van Gogh could no longer hide, the end of 1888 found Vincent van Gogh near death.

After cutting off his own left ear (all or part remains disputed) and presenting it to a local prostitute, Vincent was left nearly bloodless and suffering from seizures. The local police found him at home the morning after the incident and carted him off to the local hospital. Vincent was diagnosed with “acute mania with generalized delirium” and “mental epilepsy” and hospitalized for a brief period.

Vincent recovered enough to return home in early January, 1889. Paul Gauguin had returned to Paris, and Vincent’s hopes of a partnership and friendship as well as his own art colony and school were gone. But despite the extreme nature of his breakdown, it is widely agreed that the breakdown itself was no surprise.

Certainly, Vincent’s time in Arles appears to have been productive and optimistic, but his ongoing bad habits indicate that his mental and physical state was far from ideal. Varying sources list Vincent’s time in Arles as unhealthy and almost manic. His work was all consuming – he painted at what can only be viewed as a frenetic pace. His personal habits were atrocious – he did not bathe regularly, drank to excess, ate only bread and coffee, smoked obsessively, slept only for brief periods, and may even have drank small amounts of turpentine and ate paint. In both a mental and physical sense, Vincent’s actions were a recipe for disaster.

Yet, it was during his time in Arles that Vincent van Gogh produced many of his greatest works. Such easily recognizable works such as Shoes and Sunflowers were products of that tumultuous time, both before and after his hospitalization. Still, Vincent could never return to a “normal” life even if he wanted to.

Vincent’s vacillations between near madness and complete lucidity began to attract the attention of his neighbors in Arles. His hallucinations and delusions began to scare the townspeople, and they ultimately submitted a petition to the local police to have van Gogh ousted from his residence. Referring to Vincent as the redheaded madman (fou roux), his neighbors had him successfully removed in March of 1889. Subsequently, Vincent lived with artist Paul Signac and then his physician, Dr. Felix Rey, but he never settled in anywhere.

In May, 1889, Vincent admitted himself to the Saint-Paul asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. He wrote to his brother, Theo, of “indescribable anguish” and a feeling of disconnect. In his new “home,” the asylum, Vincent was allotted two rooms, one for his personal use and one to use as a studio. Vincent left the asylum one year later.

Bibliography

Department of European Paintings. Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890). In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. Retrieved from http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/gogh/hd_gogh.htm (originally published October 2004, last revised March 2010).

Oxford University Press (2009). Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853–1890). Retrieved from http://www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?criteria=O%3AAD%3AE%3A2206&page_number=1&template_id=6&sort_order=1§ion_id=T033021#skipToContent

Van Gogh: The Letters Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved from http://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/

Vincent van Gogh. (2014). The Biography Channel website. Retrieved from http://www.biography.com/people/vincent-van-gogh-