By Lida Prypchan

The year 1887 seems to have been a banner year for Vincent van Gogh. That spring, after moving from his brother, Theo’s, apartment to his own room in Asnieres, Paris, Vincent became acquainted with French neo-impressionist painter, Paul Victor Jules Signac. Signac developed the pointillist style of painting, in which small dots of highly pigmented color are placed in patterns that, when viewed as a whole, form a distinct picture. Once ridiculed by artists and critics, pointillism, began to grow as a result of experimentation with the technique by some very talented artists of the late 1800s.

The year 1887 seems to have been a banner year for Vincent van Gogh. That spring, after moving from his brother, Theo’s, apartment to his own room in Asnieres, Paris, Vincent became acquainted with French neo-impressionist painter, Paul Victor Jules Signac. Signac developed the pointillist style of painting, in which small dots of highly pigmented color are placed in patterns that, when viewed as a whole, form a distinct picture. Once ridiculed by artists and critics, pointillism, began to grow as a result of experimentation with the technique by some very talented artists of the late 1800s.

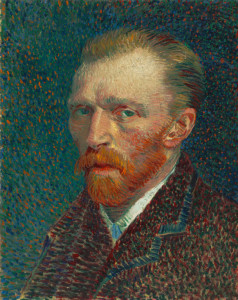

Along with French post-impressionist, Emile Henri Bernard, Vincent adopted some of the techniques popular in pointillism, including the use of complementary colors, many of these brighter than van Gogh used in his previous works. However, still a slave to his preferred somber color scheme, Vincent painted his Self Portrait in 1887 using the pointillist technique.

It is van Gogh’s exposure to an incredibly talented group of contemporaries – and maybe even more importantly, his acceptance by them – that may be viewed as the artistic breakthrough that catapulted him from mere painter to iconic artist. It must be mentioned that some researchers consider the Potato Eaters era (c. 1885) as his inception to greatness, and one must certainly recognize that those years set the stage, but it cannot be denied that his two-year jaunt with the greats of France influenced Vincent in a way that Dutch techniques had failed to inspire.

Previously, the use of light and color had been somewhat absent from Vincent’s paintings. After all, it was the Impressionists that made use of such techniques in a way that Realists had not yet explored. Learning and sharing with artistic contemporaries such as Paul Gauguin, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Emile Bernard, Camille Pissarro, and John Russell was a school for Vincent like no other.

Van Gogh’s contemporaries began to sell their first paintings, but van Gogh himself was still unable to sell his work. Vincent and Paul Gauguin exchanged some of their work, likely seeking approval, accolades, and support from one another. The group, as friends, posed for one another. They practiced, exchanged ideas, and ultimately, grew to be the great artists we recognize them as now.

The artist friends also argued about the purpose of art, techniques, and other art-related topics with Vincent being arguably the most passionate participant in these debates. Like his brother Theo earlier, Vincent’s friends found him difficult to be around. Some were even alienated by Vincent’s behavior and temperament. It is said, however, that Paul Gauguin shared a similar temperament, and Paul and Vincent remained friends.

In the winter of 1887, with his usual run down physical state that included malnutrition, exhaustion, and a chronic cough, Vincent was ready for a move. Leaving Paris for Arles in early 1888, after a productive two years in Paris – he painted over 200 works while in Paris – Vincent hoped to set up an artist’s colony with Gauguin and other artists.

Bibliography

Department of European Paintings. Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890). In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. Retrieved from http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/gogh/hd_gogh.htm (originally published October 2004, last revised March 2010).

Oxford University Press (2009). Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853–1890). Retrieved from http://www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?criteria=O%3AAD%3AE%3A2206&page_number=1&template_id=6&sort_order=1§ion_id=T033021#skipToContent

Van Gogh: The Letters Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved from http://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/

Vincent van Gogh. (2014). The Biography Channel website. Retrieved from http://www.biography.com/people/vincent-van-gogh-9515695.