By Lida Prypchan

In most books about how to improve memory the authors depict memory as a file with many drawers where we can classify and select what will go in each.

In most books about how to improve memory the authors depict memory as a file with many drawers where we can classify and select what will go in each.

We memorize something in a better or worse way, depending on the favorable or unfavorable impression that it produces in us.

How can we not be interested if almost a quarter of our life vanishes seated at a desk? Six years in elementary school, five years in high school, five years in college, and two or three years in graduate school. In total, there are somewhere between 18 to 20 years of study. Nevertheless, although study becomes a very important activity in the life of a young person, it still does not receive the attention it requires.

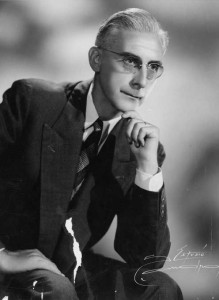

Precisely on topics such as teaching and study techniques of colleges students is what Juan David García Bacca spoke of in an interview with Ramón Hernández on June 15th of this year for the newspaper El Nacional.

García Bacca is Basque and has lived in Venezuela for 32 years. He is a philosopher. He is retired. In 5 years, he translated all the works of Plato from Ancient Greek. They total eleven volumes. To do this, it is necessary to be a philosopher and to write well.

His first criticism is about teachers. According to him, teachers believe that upon getting their degree they don’t have to study any more. This is why they give classes with knowledge that during their era was current but for ours is outdated. For him, a good teacher is not the type who teaches the same class for twenty years, but instead the type who gives his students current knowledge.

With regard to teachers, García Bacca generalized too much. There are teachers and there are teachers and, as in any other profession, there are those who are incompetent and those who are prepared, who are up-to-date, and who go to great lengths to keep students abreast of all the recent changes.

It would be interesting to do a study on this, to see what percentage of teachers teach as if they were in 1935 and how many teach according to the time in which we are living.

Undoubtedly, those who teach according to the current time will make their classes more pleasant while those who have their sights set on 1935 will make their classes a martyrdom, a slow death for students who are searching for the smallest detail to distract them.

Speaking of which, I remember in high school an older teacher who gave me lessons on the history of Venezuela. He conducted the class as if we were living in the Independence Era. His class was so boring that even he yawned.

More serious is the situation involving the students: we are in such a rush to graduate, and rush as we may, we are still left with thousands of unimportant things undone.

We study two or three days before the test, if possible we do not sleep the night before and we are very confident that because of the sleepless hours the subconscious mind will issue forth the vague knowledge we have. To develop a good study method, there is no other way to obtain it than by constantly studying. It’s like a sport. If we want to do well, we have to practice it, daily if possible.

There are many factors that turn us off to studying.

From a young age we are constantly pressured to be the model child, the one who gets good grades. A child is taught that his intelligence is measured by his grades.

To get good grades, the teacher teaches him to copy verbatim, without making him understand what is in a book.

Since the method of rote learning yields such good results and because our parents and peers flatter and admire us for being such brilliant students, we continue studying as usual. The same happens in high school, but when we stumble across a teacher who makes us think, a great catastrophe happens: the genius child is traumatized.

When he starts college and sees that to continue getting A’s he has to memorize three volumes of a thousand pages each in three months more than just one curse word leaves his mouth, once so sacred and pure.

Sooner or later he will realize his mistake and will change his study technique.

This change is difficult, but with perseverance is achievable. It consists of breaking the old habit and strengthening the new one. Some will not succeed and stagnate.

All this depends to a large degree on the parents. If from an early age the opposite habits are instilled in us and if we are warned against all of these bad habits, they will save us from more than one disappointment.

García Bacca also spoke of the comfort that there is in Venezuela for everything. He states, “In Venezuela, there is nothing to be bothered by: it rains oil and the overall atmosphere is comfortable.” If a test is difficult then it is suspended, and if the authorities do not want this, the students hold the Dean captive. They burn a bus as if lighting a cigarette. On the other hand, we want to solve everything by importing books and machinery. They bring a computer and since nobody cares about learning how to use it, it dies of laughter in one corner and us in another.

García Bacca states, “In a well-fed and well-dressed society, to ask someone to pay attention to his career and if his job requires internal reconstruction, it cannot be achieved by decree or by order from anyone. An illness is not cured in one instant, but instead it is the cells that repair the organism. This is precisely what happens in society. It is cured by certain cells of highly trained individuals that multiply. For example, a teacher manages to reach out to three students, actual students. These three reach out to nine, and so on, and by geometric progression after twenty years we will have a viable organism. But this does not happen because we are always in a hurry and looking for miracles. We believe that by saying, “Mend your ways, Venezuela. Venezuela’s ways will be mended.”

What does García Bacca recommend for us?

He recommends patience. For him this means, “withstand one hour, two hours; one year, several years.”

In the interview, García Bacca jumps from harsh criticism, (“without mincing words”) to the suffering brought on by the fatigue of his words and he ends up talking to us about melancholic patience.

In the last part of the interview, the importance of isolation and Eastern philosophy was talked about.

On these subjects, he arrived at the following: Ramón Hernández, who interviewed him, seeing this whole situation as a crisis, asked García Bacca what was the reason for this, to which he replied that he was not Encyclopedia Britannica, that all he knew was that to do something in this world one had to devote oneself to one thing alone and reduce the rest to a minimum. Then he got to the point of whether to isolate oneself or not. García Bacca said without hesitation, “If you do not isolate yourself, you end up doing nothing; the community absorbs you. At this time, the interview short circuited because the interviewee refused to explain his statement.

His indecision was noted. Cleverly, he knew how to escape this, clarifying that one is not only devoted to thought, but rather that one writes his ideas and the results of his research, and sooner or later these are in the hands of the community. “Total isolation does not exist.”

Finally, Eastern philosophy was discussed. He said that if this philosophy prevailed in the world, there would be no electronics, nothing modern would exist, not even electricity. In his opinion, this philosophy is a pleasant tale but nothing more. Poetry, pretty poetry.

For these reasons, the words of García Bacca should not be put in the bottom drawer of our memory.